Deborah Hayden

In the medieval and early modern periods, professional medicine in Ireland and Gaelic-speaking Scotland was, like other vocations such as poetry, law and history, the preserve of several learned families who exercised their occupation on a hereditary basis and were responsible for the compilation and copying of texts for educational and reference purposes. The surviving manuscripts produced by these individuals, which number in excess of 120 separate codices now preserved in repositories across Ireland and the UK, contain works dealing with a wide range of topics such as anatomy, disease, herbalism and preventive medicine. Many of these texts are translations or adaptations of well-known Latin treatises used in the curricula of the early continental universities, but there are also numerous collections of cures and charms that reflect efforts to adapt mainstream European medicine to local needs and traditions. Marginal notes left by the scribes of the Irish medical manuscripts indicate, moreover, that many medical scholars travelled considerable distances both within the Gaelic world and further afield to access new material or receive training. Since Maynooth University is the home of the LEIGHEAS project, however, it seems fitting to begin this blog series on premodern Irish medicine by introducing some written sources associated with County Kildare.

One example is the manuscript now known as Egerton 89, preserved in the British Library, which consists of 183 vellum folios and contains a fine copy of the Irish translation of the Lilium medicinae by Bernard of Gordon (ca 1258–1308), a master at the faculty of medicine in Montpellier. Bernard’s text provides, in 163 chapters, details about the definition, names and kinds of various diseases, as well as accounts of the anatomy of the affected organs, the causes, diagnosis, symptoms and prognosis of the disease, and finally treatments and a clarification of contradictions among different authorities. The Lilium was a hugely popular text: the original Latin version survives in more than 50 manuscripts and 6 printed editions, and it was translated into several vernacular languages (including French, German, Hebrew, and Spanish) during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It was also listed as required reading for students at the Universities of Montpellier and Vienna at this period. An Irish translation of the work was completed by the Ulster medical scribe Cormac Mac Duinnshléibhe by the mid-fifteenth century. Numerous copies of and excerpts from the text survive in Irish manuscripts, but they have never been edited or studied in detail.

Standish O’Grady argued on palaeographical grounds that Egerton 89 was written in Clare by Domhnall Albanach Ó Troighthigh, apparently a member of the eminent Munster medical kindred of that name. A note on folio 92 gives the year of writing as 1482. Nearly two decades later, however, the manuscript appears to have made its way further afield, as evidenced by yet another note observing that Gerald Fitzgerald, eighth earl of Kildare, paid the significant sum of 20 cows for it in 1500:

Oraid do Geróid iarla do cennuid in lebarsa giuisdis na hErinn air fichit bo da caiterni ocus fiche ata annsa lebarsa cís urmuman ar techt docum in hiarla se fichit bo in la do sgribadh in comairem so Tomas O Mailconaire do tóg in cis sin do’n iarla [ms. do hiarla] bliadain na gras (sic) in bliadainse a fuilim mile bliadain ocus cuic cét bliadan áis in tigerna nemdha in tan sa (ocus is fír sin tuas uile).

‘A prayer for Earl Garrett [Gerald] that bought this book (Justice of Ireland) for a score of kine. Two and twenty quaternions are what this book contains. The rent of Ormond, six score kine, just come in to the Earl on the day when this reckoning up was written. Thomas O’Mulconry it was that for the Earl lifted such rent. This year in which I am is the year of grace one thousand and five hundred years, [such being] the Heavenly Lord’s Age at present (all of which above is true).’[1]

The Kildares were well-known collectors of Irish manuscripts, as shown by two surviving inventories of their extensive library preserved in British Library, MS Harley 3756 (‘The Kildare Rental’). Most of the books in this library were housed in Maynooth Castle. Curiously – in light of the amount of wealth with which the earl was willing to part in order to obtain it – no mention is made of Egerton 89 in the inventories, and it is not certain that it was kept with the other books at Maynooth. A copy of Bernard of Gordon’s translated medical text would, however, have been at home in the multilingual collections of the earls of Kildare, which also included a copy of the Hortus sanitatis, a Latin encyclopedia describing the medicinal uses and preparation of various natural substances that was published by Jacob Meydenbach in Mainz, Germany in 1491, and an English rendering of Johannes de Mediolano’s Regimen sanitatis Salerni, a popular text on health regimen.

Whatever be the case regarding its possible sojourn in Kildare, Egerton 89 seems to have been returned to Clare by the early eighteenth century. Thus two notes on folios 104 and 194 state that it was in the possession of one Charles Hickey, living in Clonloghan, Co. Clare, while yet another note on fol. 12 observes that by 1728, the manuscript had passed into the hands of the dochtúir leighis (‘doctor of medicine’) Mathghamhna Mac Mathghamhna, who had spent 14 years studying in Paris.

Another copy of the Irish translation of Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium medicinae survives in Royal Irish Academy MS 3 C 19, written in 1590 by Risteard Ó Conchobhair (1561–1625). This scribe had studied at the school of the physician Donnchadh Óg Ó Conchubhair at Aghmacart, a townland about a mile to the west of Cullahill Castle, Co. Laois, then the seat of the Mac Giolla Phádraig dynasty. Donnchadh Óg was chief physician to Fínghin, third Lord Baron of Upper Ossory, and Risteard notes that he began copying Book 1 of the Irish Lilium at Cullahill Castle itself.

As Paul Walsh observed many years ago, the numerous scribal notes that accompany Bernard of Gordon’s work in the 3 C 19 manuscript provide valuable evidence for the life and methods of Irish medical scholars in the sixteenth century, as well as insight into networks of patronage in Leinster and aspects of family and local history in this region. On fol. 116, for example, the 29-year-old Risteard – who laments that his parents are dead and that he has no wife or home – observes that he finished copying the third Particle of the Lilium on the 18th of November, and that ‘far distant from one another are the places in which this book was written’ (is imchian a chéle na hionaid i nar sgriobhadh in leabhar so).

Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 3 C 19, fol. 116r: an Irish translation of Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium medicinae, with a note detailing the scribe’s whereabouts (image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen).

Among the places Risteard visited while writing his text are several locations in Co. Kildare, which are mentioned along with details about his numerous hosts and their families. It is worth reproducing Walsh’s edition and translation of this note in full here to give a flavour of the historical and genealogical riches that can be found hidden in the surviving Irish medical manuscripts:

A thinnsgnadh a gClainn Fheoruis a gCluain Each a ufochair Sheoin Óig Ailín agus a mhna .i. Mairghreg Dairsighi. Agus asin dam go Baili in Fhedha a ufhochair in Chalbhuidh mhic Í Mhordha agus a mhna .i. Mairghreg inghen in Sgúrlógaigh. Agus asin dam go Carraig Fheoruis dionnsaighi Edvaird meic Vaiteir mhic Sen Meic Fheoras .i. fiorchara agus brathair dhamh fen. A ben .i. Esibél Hussae inghen Mhaoilfhir. Ainnsidhe go Dún Uabhair dham. Lucht in Dúna sin .i. Sémus mac Gerailt mic Seáin mic Uilliam Oig mic Thomáis .i. mac mic Thomáis Geraltaigh ó Choild na Cúirti Duibhi in tUilliam Óg sin. A ben .i. Mairgreg inghen Remuinn Óig meic Tomáis .i. enduine uasal dob ferr do shliocht Seoin meic in Iarla an Remann sin agus fos ní mor go raibh fer comardaidh ris do Geraltachaibh Laighen uili i na aimsir fen. As sin dam go Baile Phollaird dionnsaighe meic maith oidhreachta na lanaman maithi sin agus enduine is annsa liom fen go beg ar an domhan in mac sin .i. Uilliam a ainm. A ben .i. Elínóra inghen tSeoin Mhic Valrónta. Agus as sin go hAlmain Laighen dionnsaighi Geroid mhic Philip mhic Muiris. Do shliocht in Rideri Chiarraidhe eside agus ní haithne damsa a gcundae Cille Dara in tan so tighisach is ferr ina é. A ben .i. Mabel inghen tSeoirsi Mhic Gerailt. Go Dun Muiri dham. Lucht in bhaili sin .i. Edvard Hussae mac Maoilir o Mhaolussaoi. Duine uasal craibhtheach daonnachtach do rer a acfuinge. A ben .i. Máire inghen in Chalbaigh mic Taidhg mic Cathaoir Í Chonchubhair .i. siúr agus cairdes Crist dam fen. (I)s a (gcundae C)illi Dara ata (na ba)ilti sin ad(ubhramar).

‘I commenced [writing] in Clann Fheoruis at Cluain Each, and in the house of John Og Alye and his wife Margaret Darcy. From there I went to Baile an Fheadha, and stayed with Calvagh, son of O More, and his wife Margaret, daughter of Scurlock. And from there I went to Carraig Fheoruis to Edward, son of Walter, son of John Mag Fheoruis (Birmingham), a true friend and a kinsman to me. His wife is Isabella Hussey, daughter of Meyler. Then I went to Dun Uabhair. These are they who live there, namely, James, son of Gerald, son of John, son of William Og (son of William), son of Thomas (this William Og was grandson of Thomas Fitzgerald of Coill na Cuirte Duibhe) and his wife Margaret, daughter of Redmond Og, son of Thomas. This Redmond was the best nobleman of the descendants of John, son of the Earl, and also it is improbable that there was any of the Fitzgeralds of all Leinster in his own time comparable to him. From there I went to Pollardstown to the good heir of that couple, namely, William, and that same son is my dearest friend in all the world except a few. The wife of William is Elinora, daughter of John Mac Valronta. And thence I went to Almhain Laighean to Garrett, son of Philip, son of Maurice. He is of the family of the Knight of Kerry, and I know not in the county of Kildare at this moment a head of a house more hospitable than he. His wife is Mabel, daughter of George Fitzgerald. Next to Dun Muire. These reside in that place, namely, Edward Hussey, son of Meyler of Mulhussey, a gentleman pious and charitable according to his means, and his wife Mary, daughter of Calvagh, son of Tadhg, son of Cathoir O Connor, a kinswoman and a sponsor in baptism to me. All these places we have mentioned are in the county of Kildare.’

From this, we know that Risteard spent time in the barony of Carbury, Co. Kildare, and more specifically at Clonagh in the parish of Cadamstown (Cluain Each). He also travelled to Donore (Dún Uabhair) in the parish of Carragh; to Pollardstown (Baile Pholaird) near Newbridge; and to ‘Allen of Leinster’ (Almhain Laighean), a location made famous by its association with the vast body of literature dealing with Fionn mac Cumhaill. Risteard’s patrons were many and varied, including several prominent members of the English and Irish gentry of the region.

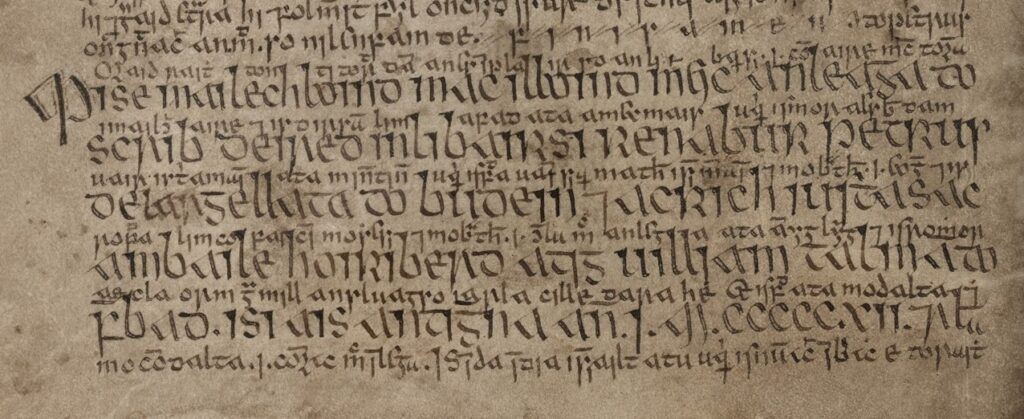

Occasional hints of activity by medical scribes who either lived in Kildare or travelled there, perhaps to obtain texts not available at home, are also found in other surviving Irish manuscripts. For example, a colophon in King’s Inns Library MS 15, a medical manuscript written in 1512 by the North Connacht doctor Máel Eachlainn Mac an Leagha – who was ollamh or ‘professor’ of medicine to the two Mac Donnchaidh lords in Co. Sligo – notes that he had finished copying his Irish translation of a surgical tract by the fifteenth-century Italian physician Petrus de Argellata ‘in the Eustaces’ Country in Herbertstown (Co. Kildare) in the house of William Tallon’ (a crich Iustasach a mBaile Hoiriberd a tig Uilliam Talman do forbad).

Dublin, King’s Inns Library MS 15 (1512): Scribal colophon by the Sligo physician Máel Eachlainn Mac an Leagha, written during a visit to Kildare. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

National Library of Ireland MS G11, which is the largest surviving Irish medical compendium (see our Manuscript of the Month entry here), is associated with the Ó Bolghaide family of Leinster, and its main scribe, Donnchadh Ó Bolghaide, notes that he began copying a treatise on general pathology in his family home, which may have been at Woodstock near Athy. Some 80 years later, his kinsman Éamonn Ó Bolghaide appears to have written part of another Irish medical manuscript (now National Library of Ireland MS G8) in the same location.

National Library of Ireland MS G8, p. 29: Beginning of an Irish translation of the ‘Aphorisms of Hippocrates’. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

While the majority of the texts in the surviving Irish-language medical manuscripts have yet to be published or studied in depth, scribal notes such as those outlined above can provide valuable clues regarding the connections between these various sources and the importance accorded to medical material by physicians and book collectors alike. One of the aims of the LEIGHEAS project is to explore these connections in more depth, while also investigating the nature of the medical texts themselves and their place within the wider context of premodern Irish textual culture and scientific learning. Stay tuned for more next month!

Further reading:

Byrne, Aisling, ‘The Earls of Kildare and their Books at the End of the Middle Ages’, The Library 14/2 (2013), 129–53

Demaitre, Luke, Doctor Bernard de Gordon: Professor and Practitioner (Toronto, 1980)

Gillespie, Raymond, ‘Scribes and Manuscripts in Gaelic Ireland, 1400–1700’, Studia Hibernica 40 (2014), 9–34

Nic Dhonnchadha, Aoibheann, ‘The Medical School of Aghmacart, Queen’s County’, Ossory, Laois and Leinster 2 (2006), 11–43

Ní Shéaghdha, Nessa, Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in the National Library of Ireland, Fasciculus I (MSS G1–G14) (Dublin, 1967)

O’Grady, Standish, Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in the British Library [formerly British Museum], Vol. 1 (London, 1926; repr. Dublin, 1992)

Walsh, Paul, ‘An Irish Medical Family – Mac an Leagha’, in Irish Men of Learning. Studies by Father Paul Walsh, ed. by Colm Ó Lochlainn (Dublin, 1947), pp. 206–18

Walsh, Paul, ‘Scraps from Irish Scribes’, in his Gleanings from Irish Manuscripts, 2nd ed. (Dublin, 1933), pp. 123–52

[1] The passage is edited and translated by O’Grady, Catalogue, pp. 220–1.