Siobhán Barrett

The Irish medical manuscripts include evidence for the wide variety of products used as ingredients in medical remedies. Exotic-sounding minerals and strange animal products are included but they are vastly outnumbered by the ingredients which were derived from plants, in particular native Irish plants, including trees, which are the inspiration for this month’s blog. The economic importance of trees is hugely significant, along with their use to provide food for humans and animals. Their wood was a vital resource as a building material for housing and fencing, for agricultural and domestic tools, and very importantly for fuel.

There are references to trees in early Irish literary texts and also in legal and medical texts. The seventh-century Old Irish law text Bretha Comaithcheso (‘The Laws of Neighbourhood’) describes the legal obligations of farmers and outlines the compensation that is due when damage is caused to the property of neighbouring farmers (Charles-Edwards 2022). One section of this law text, now known as ‘the Old Irish Tree List’, which may have originated in the lost law-tract Fidbretha (‘Tree Judgements’), categorises trees into a hierarchy of four groups: Airig fedo (‘nobles of the wood’); Aithig Fedo (‘commoners of the wood’); Fodla Fedo (‘lower divisions of the wood’); and Losa Fedo (‘bushes of the wood’). There are seven trees in each of these groups and the text details fines due for damage caused to trees. All of the twenty-eight trees in the Old Irish Tree-List are native to Ireland.

At least two other tree lists survive that may have been derived from this one, the first one in a passage explaining how the letters of the ogam alphabet were named after trees from a text called Auraicept na nÉces, ‘The Scholars’ Primer’. This also lists four categories of trees that are very similar to those in the Old Irish Tree-List but there are only twenty-five in this list, one for each letter of the ogam alphabet. The second text, naming thirteen of the trees, is an incomplete poem that has been called a summary of Bretha Comaithcheso (Binchy 1971). The modern Tree Council of Ireland also lists twenty-eight native species which are fundamentally the same as the first three categories of the Old Irish tree-list.

Since the subject matter of the LEIGHEAS project is medical texts, I have used the Old Irish tree list as my guide in the search for recipes which use tree parts. I confined my search to a collection of remedies written primarily by the North Connacht physician Conla Mac an Leagha and now preserved in two sixteenth-century manuscripts: Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MSS 24 B 3 (445) and 23 N 29 (467). The existence of these remedies is not evidence for their widespread use and I do not recomend that you try these at home.

AIRIG FEDO, NOBLES OF THE WOOD

The nobles of the wood are: dair, oak; coll, hazel; cuilenn, holly; ibar, yew; uinnius, ash; ochtach, Scots pine; and aball, wild apple.

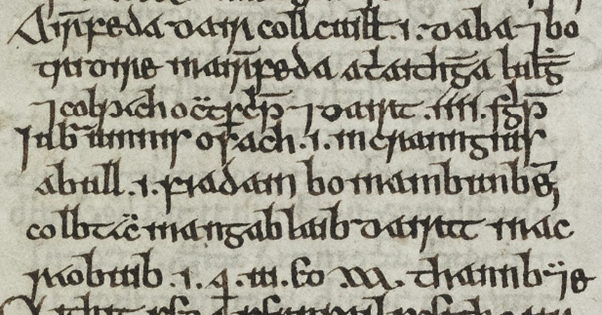

Trinity College Dublin MS 1336, col. 309: The beginning of one of the copies of the Old Irish tree list, containing the names of the trees in the first category (image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

1) DAIR, OAK (eDIL s.v. 1 dair)

The oak tree was valued for its excellent timber; its acorns, which were used to fatten pigs; and its bark, used for tanning leather (Kelly 2000, pp. 381–2). There are at least thirty-seven instances of parts of oak being used in the collection of medical remedies examined here, including bark, shavings of wood, inner bark, acorns, oak galls and juice. Ingredients derived from oak are prescribed for a wider range of ailments than any of the other trees and are recommended to treat the liver, spleen, bowel, stomach, grey hair, baldness, scabies, wounds, ear infections, nosebleeds, coughs, rapid heartbeat, breathlessness, stone, dropsy, inflammation, haemorrhoids, hernia, cancer, and erysipelas. This example is to treat vomiting:

Ar in cétna .i. etursnam darach do bruith ⁊ ebar ⁊ īcaid. (RIA 23 N 29, fol. 3r23–4)

‘For the same thing [preceding remedies are for vomiting], boil the inner bark of oak and it is drunk and it heals.’

2) COLL, HAZEL (eDIL s.v. 1 coll)

Hazel trees are valued for their nuts and because hazel rods are strong, pliable and quick-growing they were widely used in the construction of fences, enclosures and house-walls (Kelly 2000: 382). Hazelnuts and bark are the parts which are used as ingredients in remedies recommended as cures for head wounds, ear infections, stone, vomiting, cancer, erysipelas and seizures. A text called a quid pro quo, which gives a list of possible substitutes for ingredients, includes the advice that Gaelic nuts (hazelnuts) can be used instead of French nuts (walnuts) (ar son na cnó francach na cnó gaidela; RIA MS 24 B 3, p. 100.19). The example I have given below includes the shavings of eight different trees and one flower – nine ingredients in all – and the resulting liquid has to be drunk over a period of nine days. This instruction to continue with a treatment for nine days is one that is found in many medieval remedies:

Ar lūas craide ⁊ argabāil anāla .i. gloriam ⁊ casnaide cuill ⁊ cuilind ⁊ caorthuind ⁊ darach ⁊ droigin ⁊ fida[i]t ⁊ crand fir ⁊ critaigh do bruith ar lemnacht ⁊ a ōl gu cenn nómaide. (RIA MS 24 B 3, p. 67.11–13)

‘For rapid heartbeat and for catching of breath (breathlessness/asthma?) i.e. boil iris and shavings of hazel and holly and rowan and oak and blackthorn and wild cherry and juniper and aspen in milk and drink for nine days.’

3) CUILENN, HOLLY (eDIL s.v. cuilenn)

According to Bretha Comaithcheso, the holly tree is valuable because it can be used as a substitute for grass and chariot shafts are made from it. While its use as a chariot shaft is self-explanatory, Fergus Kelly (2000, 382) clarifies that it may have been fed to cattle in winter months instead of grass, because the leaves of the upper branches are not as spiny and are therefore more palatable than those of the lower branches.

In medicine, the bark and berries of holly were used to cure worms in the bowel, headache, head wounds, bad breath, asthma/breathlessness, stone, coughs, rapid heartbeat, weakness of the heart, vomiting and impotence. The following remedy is for asthma and diarrhoea:

Cosc ar mūchad ⁊ ar lir .i. crotoll fraich ⁊ crotoll cuilind ⁊ caerthaind ⁊ a rusc ⁊ espericum beaain ⁊ gleōrān ⁊ berbtur ar chuirm nó ar lemnacht ⁊ ebar fōs ar cétlongad. (RIA MS 24 B 3, 62.15)

‘To prevent asthma and diarrhoea, boil rind of heather, holly and rowan along with its bark, and St John’s wort and gleorán and it is boiled in beer or in fresh milk and also it is drunk when fasting.’

4) IBAR, YEW (eDIL s.v. ibar)

Although the yew is a native tree and is still sometimes found in old forests, yew trees are most often seen now in cemeteries and churchyards. According to the commentary on Bretha Comaithcheso, the yew tree’s importance lies in its valuable artefacts and there are references in early Irish texts to yew vessels (Best 1910, 134). Most parts of the plant are poisonous if ingested but the following remedy is used topically as an ointment or cream for scrofula, a swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck caused by a bacterial infection, usually tuberculosis:

Ar espaib: barr ibair brister cia min ⁊ cur tre psengruidin ⁊ a cur orro-som. (RIA MS 24 B 3, 59.25)

‘For scrofula: crush the shoots of a yew tree until fine and mix through old curds and put [it] on them (the swellings)’.

5) UINNIUS, ASH (eDIL s.v. uinnius)

The wood of the ash tree was used for furniture. According to Bretha Comaithcheso it was used as folach rígshlíasta ‘support for a royal thigh’, presumably a chair of some kind (Charles-Edwards 2022, 292–3). It is a very strong wood, but lightweight, making it suitable for use as the shaft of weapons and its good capacity for shock absorption makes it the favourite material for hurleys. In the medical manuscripts, its ashes were used for the production of lye, which was used externally as a lotion to treat skin problems, infestations of mites, scabies, cancer and leprosy. Its juice was drunk to treat problems of the spleen and, in the following remedy, for deafness:

Ar buidre: gaub sūg tic a cend made uinsend bīs ar tene lāun blaisci uighe de. ⁊ dā lān lege argit d’em ⁊ aenlāun legi do sūg fīrlosa ⁊ dá lān do zūg teneguil ⁊ aenlān legi do mil glan ⁊ dá lege do bainne cíchi mnā ailes mec. ⁊ tēter gurub ellte ⁊ cuir nī de isin clúais ⁊ dūntur ’na diaig. (RIA MS 24 B 3, p. 48.5–8)

‘For deafness: take the juice that comes from the top of an ash stick which is on a fire, an eggshell-ful of it. And two silver spoons of butter, one spoonful of juice of leeks, and two full of juice of house leek, and one full of clean honey, and two full of breast milk of a woman who is nursing a boy. And it is heated until warm, and then put some of it in the ear and it is closed afterwards.’

6) OCHTACH, SCOTS PINE (eDIL s.v. ochtach)

Native pines are uncommon in Ireland and most of the pines now growing here were imported from Scotland and planted over the last 150 years. The commentary on Bretha Comaithcheso says that the value of the pine tree is ‘its resin in a bowl’ and Kelly (2000, 383) suggests that this reference to it in the law text indicates that pines were still common in Ireland in the eighth and ninth centuries. There are not many uses of pine in our collection of remedies except for a few references to pícc ‘pitch’, which was included as an ingredient for topical treatments, in an eyesalve, in a plaster for scrofula, in a poultice for a stomach problems and in this potentially painful treatment for scabies:

Ar carraige .i. pīc do lēgad ar bhrēid ⁊ a cur te [i]mon cenn ⁊ a lēgur air gu fāsa a fhinnfad trīt ⁊ a tarruing ar héigin de cona fhindfad. (RIA MS 24 B 3, 37.30–38.2)

‘For scabies, put melted pitch on a piece of cloth and place warm on the head. Leave it there until the hair grows through it and pull it off him forcefully with his hair.’

7) ABALL, APPLE (eDIL s.v. aball)

The apple tree is valued for its harvest and its bark (Charles-Edwards 2022, 293). In medicine there are uses for its seeds, its juice and its bark. Kelly (2000, 383) says that the mention of bark is mysterious and that it was perhaps used as a yellow dye for cloth, but another explanation may be in its use as a medical ingredient. Sometimes there is a distinction made between wild and sweet apples; for example, rúsc ubla fiadain ⁊ ubla cubra (‘the bark of a wild apple tree and of a sweet apple tree’) are called for in one recipe. The bark is used in poultices for head wounds, for cancer, for bowel problems, eye ailments and below in a versified remedy for pulmonary ailment called loch tuile (on this term, see Hayden 2019):

Cairt caeraind, cairt chaomabla,

cairt droigin, cairt derg darach,

cairt fethlinde uindsindi,

a mbrochán biaid gu bladach. (RIA MS 24 B 3, p. 61.27–8)

‘Bark of rowan, bark of beautiful apple,

bark of blackthorn, red bark of oak,

bark of woodbine that grows on an ash tree,

their pottage will be renowned.’

To be continued…

Further Reading

- Best, Richard Irvine (1910), ‘The Settling of the Manor of Tara’, Ériu 4: 121–72

- Binchy, Daniel A. (1971), ‘An Archaic Legal Poem’, Celtica 9: 152–68

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas, ed. (2022), Bretha Comaithcheso: An Old Irish Law Tract on Neighbouring Farms (Dublin: DIAS), pp. 293–4

- Grieve, Maud (1971), A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses. 2 vols. (New York)

- Hayden, Deborah (2019), ‘The Lexicon of Pulmonary Ailment in Some Medieval Irish Medical Texts’, Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 66: 105–29

- Kelly, Fergus (1976), ‘The Old Irish Tree List’, Celtica 11: 107–24

- Kelly, Fergus (2000), Early Irish Farming: A Study Based Mainly on the Law-Texts of the 7th and 8th Centuries AD (Dublin: DIAS), pp. 379–90

- Lucas, A. T., ‘The Sacred Trees of Ireland’, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 68 (1963), 16–54

Thanks so much for making such marvellous traditions available to a modern audience.