Deborah Hayden

NB: This blog contains excerpts from a forthcoming article by the author:

Deborah Hayden, ‘The Pathology of Love in Two Medieval Irish Tales’, in Emotions, Illness and Medicine in the Medieval North, ed. by Caroline R. Batten and Sif Rikhardsdottir (Cambridge: CUP)

*******

Fig. 1: Jacques-Louis David, Erasistratus Discovers the Cause of Antiochus’s Disease (1774), École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

An episode in the medieval Irish tale known as Tochmarc Étaíne (‘The Wooing of Étaín’), the earliest surviving copy of which is preserved in a twelfth-century manuscript, recounts how Ailill Ánguba, brother of king Eochaid Airem, fell into a state of sickness and despondency out of love for his brother’s wife, Étaín. The narrator relates how:

Ailill fell into a decline lest his honour should be stained, nor had he spoken of it to the woman herself. When he expected death, Fachtna, Eochaid’s physician, was brought to see him. The physician said to him, ‘One of the two pains thou hast that kill man and that no physician can heal, the pain of love and the pain of jealousy.’ Ailill did not confess to him, for he was ashamed. Then Ailill was left in Frémainn Tethba dying, and Eochaid went on a circuit of Ireland (Bergin & Best 1938: 167).

While Eochaid is attending to his royal duties, Étaín is left to care for Ailill, visiting him every day ‘to bathe his head and to carve his meat and to pour water on his hands’ (Bergin & Best 1938: 167). After nine days, Ailill’s health begins to improve and, having finally confessed his love to Étaín, the two agreed to a tryst. Ailill fails to awaken in time to meet her on three successive attempts, however, and instead Étaín is confronted at the trysting-place with her former Otherworldly husband, Midir of Brí Leith, who claims to have orchestrated the entire series of events after he had been parted from her by sorcery. The scene ends with Étaín agreeing to accompany Midir to his land having been spared any stain upon her honour, while Ailill is in turn healed of the affliction that the Otherworldly king had visited upon him.

The central theme in this tale of passionate love (eros) experienced as a bodily illness is paralleled in a wide range of classical and biblical texts. For example, Henri Gaidoz (1912) drew attention to the similarity between the depiction of Ailill Ánguba in Tochmarc Étaíne and the account given by the first-century philosopher Plutarch in his Life of Demetrius (and elsewhere) concerning King Seleucis’s son Antiochus, who suffered from a passionate and illicit love for his stepmother Stratonice. The immorality of incestuous love that is hinted at in both the Irish and Latin narratives likewise features in the biblical account of King David’s son Amnon (2 Samuel 13), who becomes infatuated with his half-sister Tamar. When Amnon’s cousin Jonadab inquires as to why Amnon has lost so much weight, the latter confesses all, and Jonadab advises him to feign sickness and beg that Tamar be brought to care for him. Like Étaín, Tamar complies with this request and attempts to feed her ailing brother, who then confesses his love for her and urges her to lie with him.

Fig. 2: Giovanni Domenico Cerrini (1609–1681), Amnon and Tamar

Such accounts attest to the popularity of the theme of lovesickness in many different literary traditions, but medieval narrative portrayals of the disease also owe much to contemporary developments in medical learning that likewise drew heavily on earlier sources. This month’s blog will survey some key manuscript sources for the diagnosis and treatment of love in early Irish medical tradition and will consider their place within the wider framework of medieval scientific thought.

As Mary Wack has shown in her monograph study of lovesickness in the Middle Ages (Wack 1990: 6), ancient medicine offered little systematic discussion of love and it was not until the fourth century AD that love appeared as a separate classification of mental disease: before this, it was variously associated with other mental illnesses such as mania, melancholy and phrenesis (frenzy), psychological states with which it remained closely intertwined in later centuries both in terms of its nosology and therapeutics. At this period, the most sophisticated discussions of love as a disease are found in sources such as the Greek Synopsis (or Conspectus ad Eustathum) of Oribasius, physician to Julian the Apostate. Oribasius catalogued the symptoms and cures for those ‘who are consumed by love’ in Book 8 of his work, which is devoted to diseases of the nervous system. He explains that the physician can recognise patients afflicted by morbid love by the fact that they are suffering from sadness, insomnia, hollow eyes and an inability to cry, and suggests that the physician should prescribe baths, wine and listening to amusing stories or speeches in order to distract the afflicted person from their obsession. The Synopsis was an influential medical text in the early medieval West, having been translated into Latin twice around the sixth century (Wack 1990: 10). Although there is no surviving direct evidence for its transmission in Ireland during the early Middle Ages, John Contreni (1981: 338–9) has shown that much of Oribasius’s work, including the book containing his chapter on lovesickness, was available to Irish scholars working in Laon during the third quarter of the ninth century.

Fig 3: Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawl. C. 328, fol. 3r (14th century; Latin medical texts): Constantinus Africanus examines patients’ urine

A crucial turning-point in the development of medical ideas about lovesickness occurred less than a century before the copying of our earliest extant source for the narrative Tochmarc Étaíne in the twelfth-century manuscript Lebor na hUidre (Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 E 25). This was the account given of passionate love by Constantinus Africanus, a figure who was reputedly born in Carthage and travelled to Monte Cassino in Italy in the latter half of the eleventh century, where he began a programme of translation from Arabic into Latin under the patronage of the archbishop of Salerno and the abbot of Monte Cassino. Among Constantine’s many influential Latin works was his rendering of the popular medical handbook of the tenth-century Arabic physician Ibn al-Jazzar, commonly referred to in Latin as the Viaticum. This treatise is divided into seven books dealing with diseases in head-to-toe order, with ‘passionate love’ forming the subject of the twentieth chapter of the first book, immediately preceded by Constantine’s treatment of insomnia, frenzy and drunkenness. Although his discussion of lovesickness is clearly indebted to much earlier sources, Mary Wack (1990: 50) has argued that its inclusion in what was intended as a practical medical handbook for travellers cast new light on the condition as a psychosomatic disorder requiring treatment by a physician and situated it more firmly within the bounds of medical discourse, which ‘offered a new interpretive model for explaining certain symptoms of appearance and behavior.’

Constantine begins his discussion of passionate love (eros) by stating that it ‘is a disease touching the brain. For it is a great longing with intense sexual desire and affliction of the thoughts’ (Wack 1990: 187). He then details the physiological causes of the disease, explaining that it results from a need to expel an excess of humours. Citing the teaching of the first-century Greek physician Rufus of Ephesus, Constantine recommends intercourse – even with those whom the patient does not love – as being beneficial for ‘those in whom black bile and frenzy reign’ (Wack 1990: 189). This advice for curing lovesickness through intercourse had become more prominent in Arabic medical sources of the period and was a matter of some debate in many medieval discussions of passionate love as a disease. For scholars of Irish literature, however, it might readily bring to mind Ailill Ánguba’s thwarted tryst with Étaín, who had (in otherwise hard-to-explain circumstances) agreed to forego her honour as a married woman and sleep with the king’s brother in order to cure his illness: an event that was neatly side-stepped by the narrator of the Irish tale by making Ailill oversleep and curing him of his illness using Midir’s magic. Constantinus Africanus also cites ‘the contemplation of beauty’ as another cause of lovesickness, claiming that ‘if the soul observes a form (forma) similar to itself it goes mad…over it in order to achieve the fulfilment of its pleasure.’ Here, too, one is reminded of the narrator’s emphasis in Tochmarc Étaíne on how the cause of Aillil’s illness was his ‘wont to gaze at [Étain] continually, for such gazing is a token of love’ (Bergin & Best 1938: 165).

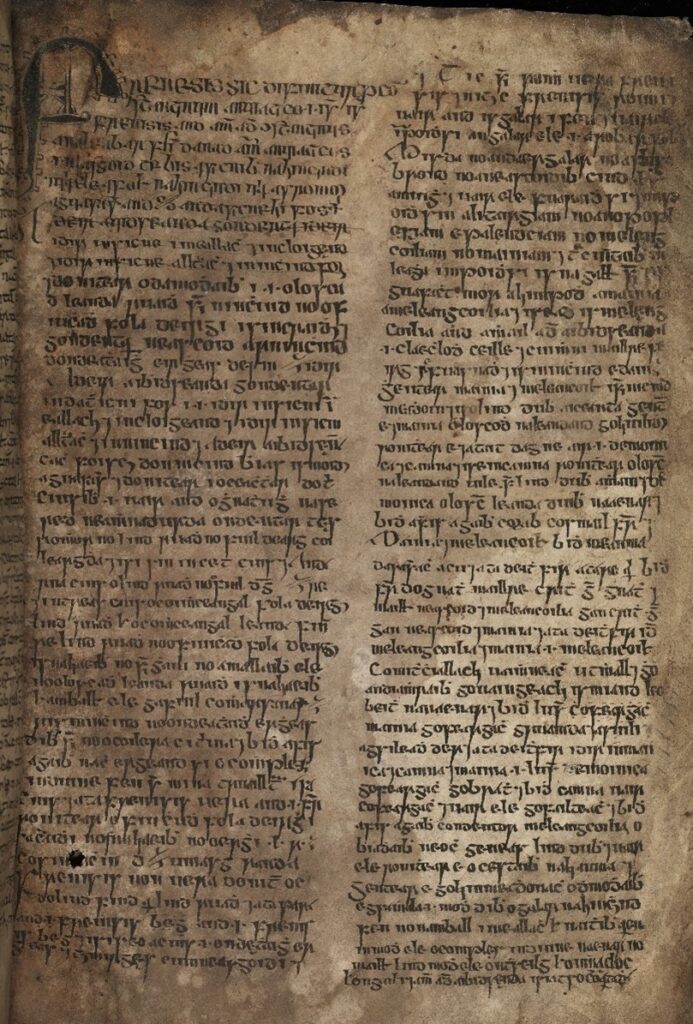

As is the case for the Synopsis of Oribasius, we have no direct evidence for the circulation of Constantine’s Viaticum in Ireland prior to the late Middle Ages, although it is possible that earlier vernacular translations of the work once existed that are now lost. For example, an incomplete and as-yet unedited Irish version of a tract on diseases, preserved in the fifteenth-century King’s Inns Library MS 17, was apparently compiled primarily from an earlier Irish translation of the Viaticum (see Figure 4 below). It begins with a three-page discussion of ‘frenesis’ that also deals with associated psychological disorders and their humoral basis, such as melancholia. As noted above, both these conditions were discussed alongside lovesickness in the first book of Constantine’s Viaticum.

Fig. 4: Dublin, King’s Inns Library MS 17, fol. 13r: An Irish tract on diseases, apparently compiled mainly from the Viaticum of Constantinus Africanus. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

Other surviving Irish medical manuscripts also contain texts that more explicitly discuss the diagnosis, symptoms and treatment of morbid love. One example is found in another fifteenth-century codex: namely, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 P 10 [ii], often referred to as ‘Book of the O’Lees’ or the ‘Book of Hy Brasil’ (on the origins of the latter name, see the excellent RIA blog here). This manuscript contains an Irish translation of the Latin Tacuini aegritudinum – itself a translation of an Arabic text by the eleventh-century physician Ibn Jazlah – containing 44 tables that provide descriptions of different diseases, detailing their names, stages, symptoms and cures. The table on p. 34 of the manuscript (see Figure 5 below) is concerned with diseases affecting the head, and the very last row, which follows descriptions of the conditions ‘melancholy’ and ‘mania’, features boxes devoted to the subject of amor .i. grádh (‘love’). In keeping with earlier medical accounts of passionate love, it is noted that a person suffering from this affliction can be identified by way of symptoms such as sunken eyes and a change in the pulse, while possible cures include distracting the patient with occupations or artistic pursuits, as well as causing them to be frightened.

Fig. 5: Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 P 10 (ii) (‘The Book of the O’Lees’ or ‘The Book of Hy Brasil’), p. 34 (15th century): a table from the Irish translation of Ibn Jazlah’s Tacuini aegritudinum. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

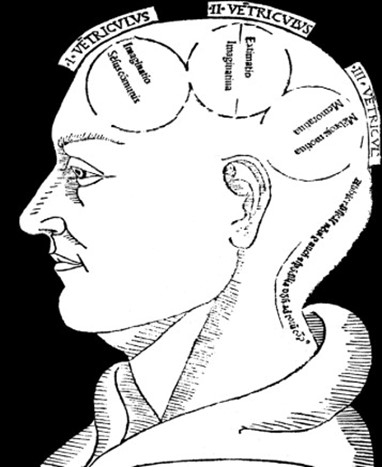

Constantinus Africanus’s discussion of lovesickness was the subject of several commentaries in the centuries after it was written, many of which sought to explain the affliction in light of contemporary theories concerning brain anatomy and the physiological basis for human emotions. Several such texts described the brain as containing three cells or ventricles situated from the front to the back of the head (as illustrated in Figure 6 below). According to the thirteenth-century English encyclopaedist Bartholomaeus Anglicus, for example, input from the world entered the anterior of the brain via the senses, while cogitation and critical thinking (including understanding the difference between fantasy and reality) occurred in the middle cell and memory was stored in the posterior brain (Turner 2021: 159–60).

Fig. 6: Diagram of the three cerebral ventricles and the mental faculties located within them, from Albertus Magnus, Philosophia pauperum (1490). National Library of Medicine, USA

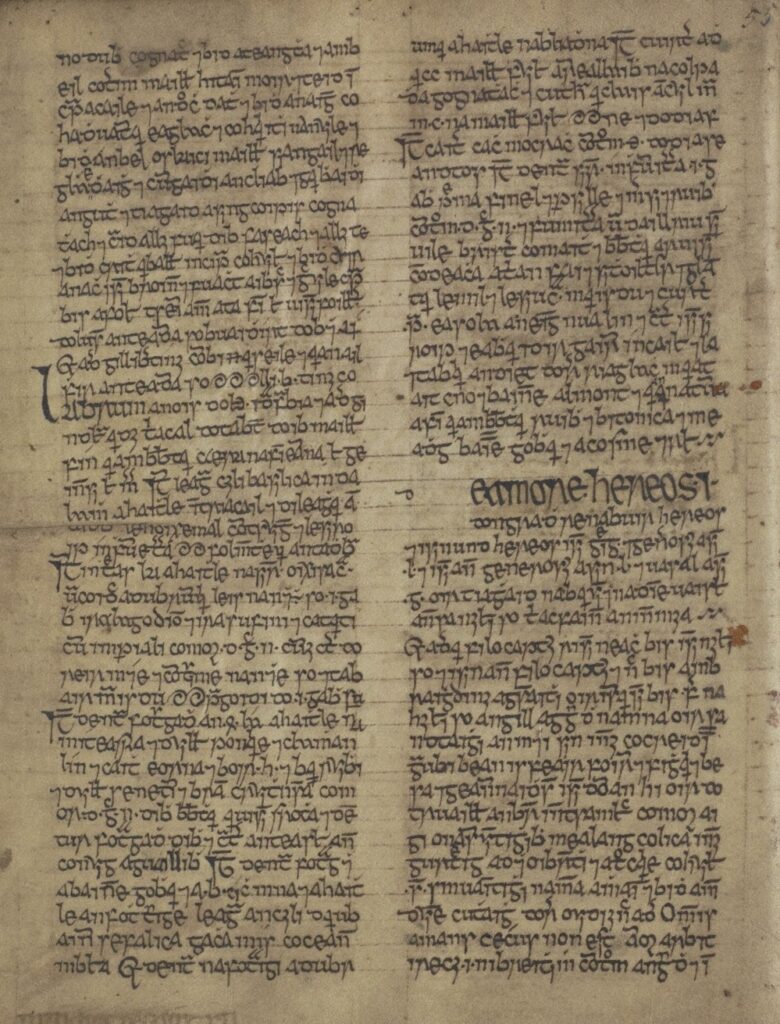

These ideas about brain anatomy are reflected in one of the most widely circulated texts on lovesickness in the Gaelic world, which is the Irish translation of the chapter on this topic in the Lilium medicinae of the thirteenth-century Montpellier physician Bernard of Gordon. The Latin Lilium was a very popular text that consisted of 163 chapters detailing the definition, names and kinds of various diseases, as well as causes, diagnosis, symptoms, prognosis and treatments. It was translated into Irish during the fifteenth century, and numerous copies and excerpts survive in the extant Irish medical manuscripts (for one such copy, now preserved in an Irish medical manuscript in the British Library, see my previous blog here). Bernard’s chapter on lovesickness seems to have been of particular interest to Irish medical scribes, however, since several copies of it are preserved independently of the rest of the Lilium in various medical manuscripts. Some of these sources also contain texts relating to wider Irish literary tradition, pointing to the broad interests of Gaelic medical scholars: for example, the copy of Bernard’s chapter shown in Figure 7 below is found in National Library of Scotland MS Adv. 72. 1. 2, a composite codex that also contains annals, commentary on the early Irish law of sick-maintenance and wisdom literature.

Fig. 7: Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, MS Adv. 72. 1. 2, fol. 81v (middle of second column): A copy of the Irish translation of the chapter on lovesickness from Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium medicinae. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

In his attempt to provide a scientific explanation for the affliction of passionate love, Bernard of Gordon stated that men tend to succumb to this disease because ‘the power of comparison’ (vis aestimativa) is so destroyed in them through their melancholy thoughts that they come to fixate on the desired woman, abandoning all other actions and occupations and ultimately become like madmen. He then outlines the workings of the various mental faculties, claiming that ‘the power of comparison recognizes [love] from the force that is called imaginativa’ (the mental faculty located in the first cerebral ventricle). The signs of love acknowledged by Bernard are reminiscent of those identified by Constantine in the Viaticum (e.g. lack of desire for food and drink; little sleep; wasting of the body; gloomy meditations; and a rapid and irregular pulse), but his cures are far more dramatic. Bernard first specifies that the doctor ‘should ascertain whether the patient be a reasonable man or an unreasonable one’; if reasonable, he can be instructed by a learned person who will bring shame upon him and ‘withdraw his mind from the false image (imhaidh fallsa) he holds’. If the man is unreasonable, however, Bernard says that the man’s clothes should be taken off him and that he ‘be beaten with scourges sorely until his skin redden’. If this does not work, Bernard instructs that ‘an unsightly hag be sent into [the man’s] presence, of evil appearance and wearing wretched garments’, who should thrust a bloody menstrual cloth in the lover’s face and declare that the man’s beloved is ‘bibulous, stinking, and has epilepsy’, that her skin is foul and covered with sores, and that the woman urinates in bed (Wulff 1932: 180–1). Such extreme (and rather misogynistic) measures were likely inspired by a type of aversive therapy that can ultimately be traced back to works of the classical period and was popularised in medieval medical tradition via its inclusion in Avicenna’s influential Canon of Medicine, an encyclopaedia of medicine in five books that was completed in 1025.

The ‘malady of love’ was a rich source of imagery and a frequently used plot motif for the authors of medieval Irish narrative texts. Such portrayals of the lovesick patient might also be read, however, against the backdrop of developments in contemporary medical teaching on this theme. The evidence from the surviving Irish medical manuscripts demonstrates that the Gaelic world was fully in step with wider ideas about lovesickness current throughout the Middle Ages, which reflect a complex interplay between classical and biblical source-material, literary creativity and scientific thought.

Further reading:

- Bergin, O. and R. I. Best, eds (1938), ‘Tochmarc Étaíne’, Ériu 12: 137–96

- Contreni, John, ‘Masters and Medicine in Northern France during the Reign of Charles the Bald’, in Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom, ed. by Margaret Gibson and Janet Nelson (Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1981), pp. 333-50

- Hayden, Deborah (forthcoming), ‘The Pathology of Love in Two Medieval Irish Tales’, in Emotions, Illness and Medicine in the Medieval North, ed. by Caroline R. Batten and Sif Rikhardsdottir (Cambridge: CUP)

- Lowes, John Livingston, ‘The Loverest Maladye of Hereos’, Modern Philology 11.4 (1914), 491–546

- MacLeod, Robbie Andrew (2024), ‘Love and Gender in Medieval Gaelic Saga’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow)

- Michie, Sarah (1937), ‘The Lover’s Malady in Early Irish Romance’, Speculum 12.3: 304–13

- Nic Dhonnchadha, Aoibheann (2009), ‘The “Book of the O’Lees” and Other Medical Manuscripts and Astronomical Tracts’, in Treasures of the Royal Irish Academy Library, ed. by Bernadette Cunningham, Siobhán Fitzpatrick and Petra Schnabel(Dublin: RIA), pp. 81–91

- Turner, Wendy J. (2021), ‘Mind/Brain: Medieval Concepts’, in Iona McCleery (ed.), A Cultural History of Medicine in the Middle Ages (London: Bloomsbury), pp. 155–75

- Wack, Mary F. (1990), Lovesickness in the Middle Ages. The Viaticum and its Commentaries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

- Wulff, Winifred (1932), ‘De amore hereos’, Ériu 11: 174–81