Sharon Arbuthnot

Fig. 1: The homepage of the electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language (eDIL).

Citations from a great variety of medical texts appear in the Dictionary of the Irish Language. These are used mainly to illustrate domain-specific vocabulary, such as slapar ‘a bandage’, alga ‘an ulcer’ and purgóit ‘a purgation; a purgative’, but they also provide examples of more mundane words and phrases. One of only a handful of citations given to support the use of caillech to mean ‘elderly woman’ is drawn from medical material in which a pulse with long intervals between beats is compared to the teeth of an old woman!

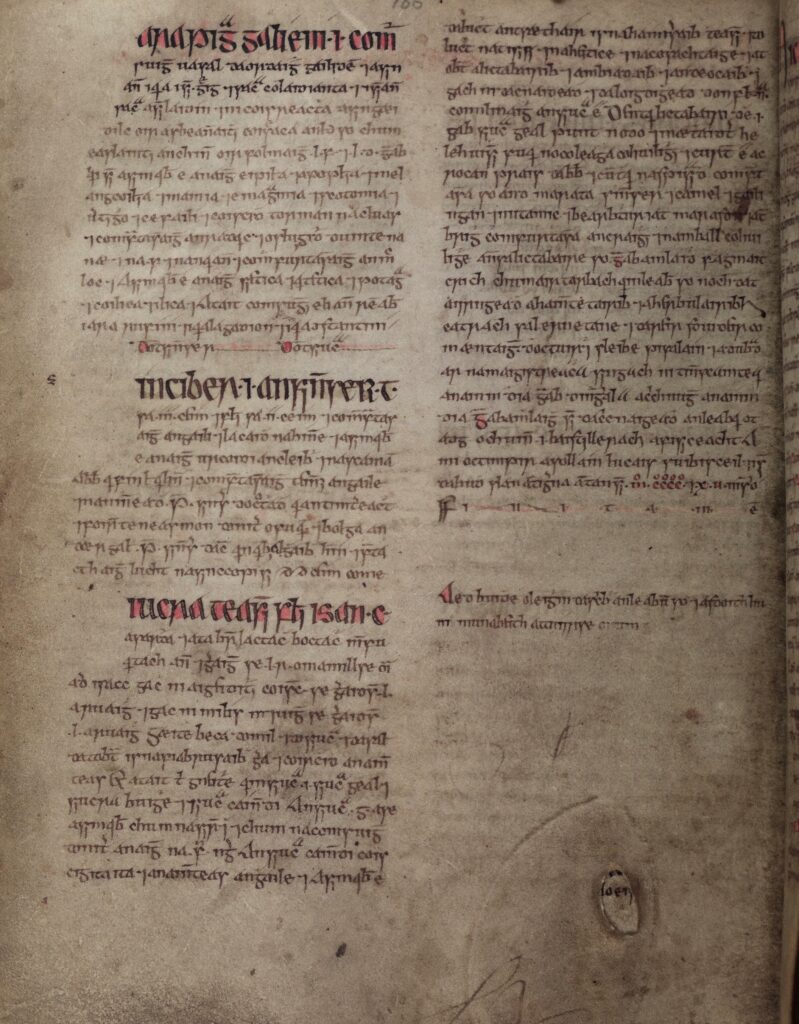

Often, it is clear from the reference given in the dictionary that the source in question is a medical text. ‘Rosa Angl.’, for example, stands for Rosa Anglica and refers to the Irish adaptation of a treatise on medicine by Englishman John of Gaddesden. ‘RSláinte’, on the other hand, denotes an Irish version of Regimen santitatis by Maino de Maineri, who was master of the University of Paris and physician to both the Visconti rulers of Milan and King Robert the Bruce. Alongside these citations from easily-distinguished sources are others which were taken directly from manuscripts and are identified only by the shelfmarks or catalogue numbers. As a case in point: ‘23 P 10’ refers to the Book of the O’Lees, a medical book which contains extracts from the works of Hippocrates as well as other texts on disease and cure. Several hundred citations from this manuscript made their way into the dictionary, but it is questionable whether all (or even most) users of that resource would recognise ‘23 P 10’ as a reference to medical writings.

Fig. 2: Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 P 10 (ii) (‘The Book of the O’Lees’ or ‘The Book of Hy Brasil’), p. 34 (15th century): a table from the Irish translation of Ibn Jazlah’s Tacuini aegritudinum (on this text, see also Deborah Hayden’s previous blog here). Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

With this in mind, a new project, entitled ‘A Chronology of the Medieval Irish Lexicon’, aims to enrich the content of the Dictionary of the Irish Language by adding titles or descriptions of the texts cited in it and providing also information on the time-periods to which those texts belong. Establishing broad dates for the medical texts is a reasonably straightforward task, for we know that scholars were translating or adapting material of this kind, mainly from Latin originals, in the Early Modern Irish period. Most medical texts were produced between 1200 and 1600, then, but it is of obvious interest to date this material as precisely as possible. In that way, we might hope to discern a distinct seam of specialised medical vocabulary running through the language, as numerous words and phrases were introduced specifically to provide Irish equivalents for Latin medical terms, and many of these seem to have been in use for only a short period of time.

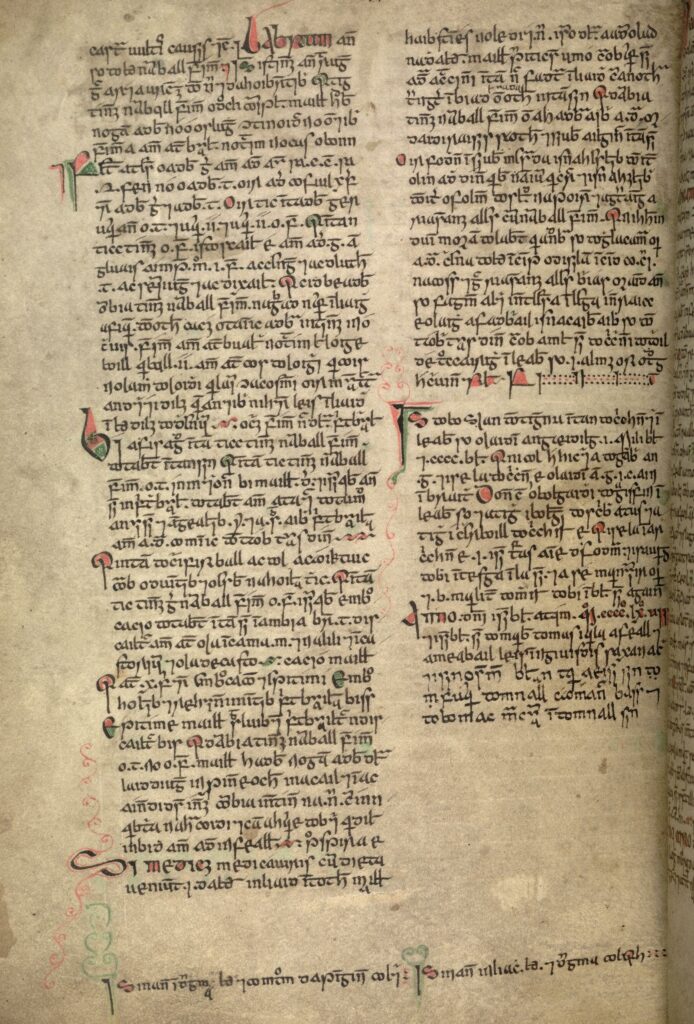

So, how do we begin to establish more precise dates for the medical texts? Fortunately, a few of the surviving manuscript witnesses include information on who translated, composed or compiled the texts and when that work was carried out. What is probably the best-known example of this kind of ‘internal dating’ can be found in Dublin, Trinity College, MS 1343 (p. 106b). Here, an initial note states that the treatise which has just come to an end was drawn from herbals and books of antidotes associated with the city of Salerno in Italy. This is followed by a separate comment which records that Tadhg Ó Cuinn finished the treatise on the 18th October 1415. Of course, Tadhg may have been involved in transmitting the text, rather than producing it, but given his insights into the sources on which the Irish material was based and the fact that he is given the title baistillerach a fisiceacht ‘bachelor of medicine’ in the adjacent comment, it is generally assumed that a substantial section of MS 1343 is Tadhg Ó Cuinn’s own work and belongs to the early fifteenth century.

Fig. 3: Dublin, Trinity College MS 1343, p. 106b, a page from Tadhg Ó Cuinn’s Irish herbal, completed in 1415. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

Even when there is no explicit information to be gleaned from a text itself, a little detective work can bring its period of origin into sharper focus. Dates of manuscripts can be used to determine upper limits for the texts preserved in them, while the dates of sources can set lower limits. To return to two important sources mentioned above: John of Gaddesdan probably completed Rosa Anglica around 1317 and Maino de Maineri’s Regimen santitatis was written in 1331. Thus, Irish versions of these works cannot have emerged before the early part of the fourteenth century. Plausible ‘windows’ for their production begin to form when we recognise that these texts are preserved in manuscripts copied in the 1460s. Extracts from Rosa Anglica regularly turn up in Irish medical compendia but perhaps their more useful context is National Library of Ireland, MS G 11. This manuscript has invaluable annotations, giving names, dates and datable events as scribes sought to leave behind some record of themselves and the principle events of their lifetime. Not only is the year 1468 noted in several places in MS G 11, but there is also a reference (p. 248b) to the beheading of Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Desmond, which confirms that date. In the case of Rosa Anglica, then, the evidence of G 11 and other manuscripts helps us establish that the temporal ‘window’ for this particular text opens in the 1310s and closes in the 1460s.

Fig. 4: Dublin, National Library of Ireland MS G 11, p. 248: An Irish translation of the Commentary of Geraldus de Solo on the ninth book of Rhazes’ Almanzor, containing a colophon referencing the beheading of Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Desmond. Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen.

Adding information of this kind, on genre and date, to citations in the Dictionary of the Irish Language will facilitate more informed reading of the entries in which they are contained. It will become apparent that names for a range of exotic products probably entered the language with medical translations: oisre ‘an oyster’, siúcra ‘sugar’ and oráitse ‘an orange’ are all first attested in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century translations of works like Rosa Anglica and Regimen santitatis. Similar sources suggest that cintaigid ‘transgresses, defaults, sins’ briefly shifted sense in this period to supply Irish with a verb which could convey the meaning ‘infects’. Looking at entries in the dictionary at present, some items of vocabulary seem unusually poorly-attested but, with the benefit of enhanced metadata, we will see that their citations are actually tightly clustered in time and confined to medical texts. Examples include gáethmairecht ‘flatulence’, diuretech ‘diuretic’, lámannán ‘bladder’ and the tantalising sceith ailt, literally ‘a joint-spew’, a phrase used to refer to a node or swelling near a joint. These terms, and others like them, make up that seam of innovative but under-researched medical vocabulary which runs through the language in the late medieval period.

The project ‘A Chronology of the Medieval Irish Lexicon’ (2023-2026) is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and based at Queen’s University, Belfast, and at the University of Cambridge.

Resources and Further Reading:

- Carney, James P. [Séamus Ó Ceithearnaigh] (1942-44), Regimen na sláinte: Regimen sanitatis Magnini Mediolanensis, 3 vols, Leabhair ó Láimhsgríbhnibh, 9, 11, 13 (Dublin: Stationery Office)

- eDIL 2019: An Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, based on the Contributions to a Dictionary of the Irish Language (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1913-1976) (www.dil.ie 2019)

- Nic Dhonnchadha, Aoibheann (2009), ‘The “Book of the O’Lees” and Other Medical Manuscripts and Astronomical Tracts’, in Treasures of the Royal Irish Academy Library, ed. by Bernadette Cunningham, Siobhán Fitzpatrick and Petra Schnabel (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy), pp. 81–91

- Nic Dhonnchadha, Aoibheann (2016), ‘The Irish Rosa Anglica: Manuscripts and Structure’, in Rosa Anglica: Reassessments, ed. by Liam P. Ó Murchú, Irish Texts Society Subsidiary Series 28 (London: Irish Texts Society), pp. 114–197

- Wulff, Winifred, ed. and trans. (1929), Rosa Anglica seu Rosa medicinae: An Early Modern Irish Translation of a Section of the Mediaeval Medical Text-book of John of Gaddesden, Irish Texts Society 25 (London: Irish Texts Society)