Siobhán Barrett

Fig. 1: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, fol. 52r (‘Codex Manesse’, 14th century CE, Zurich, Switzerland): An illustration of a medieval noble taking his bath and being attended to by servants.

Evidence for traditions and conventions surrounding washing and bathing are found in many written sources from medieval Ireland. There are descriptions of the provision of washing facilities for guests, for example, such as a ninth-century triad that describes the three desirable characteristics of a good man’s house as ‘ale, a bath, a large fire’ (Meyer 1906, 12). Several episodes in the early Irish saints’ lives point to the importance of foot-washing and bathing as part of the duties of a host. In some cases, the saint in question foresees the arrival of guests and arranges to have a bath prepared beforehand (Lucas 1965, 70). In descriptions of battles, injured warriors are given curative baths so that they can live to fight and die another day. This excerpt from Cath Maige Tuired describes how the injured champions of the supernatural race known as the Túatha Dé Danaan were healed by the skill of their physicians so that they could return to the battlefield and face their enemies, the Fomóire:

‘Now this is what used to kindle the warriors who were wounded there so that they were more fiery the next day: Dían Cécht, his two sons Octriuil and Míach, and his daughter Airmed were chanting spells over the well named Sláine. They would cast their mortally-wounded men into it as they were struck down; and they were alive when they came out. Their mortally-wounded were healed through the power of the incantation made by the four physicians who were around the well’ (Gray 1983, 55; for this and further examples, see Hayden 2024, 80-3).

Washing and bathing were regularly prescribed as part of healing therapies and therefore many words specific to washing are used in Irish medical texts. For this month’s blog, I will discuss a few examples of words for washing particular parts of the body.

Indlat (eDIL s.v. indlat or dil.ie/28463)

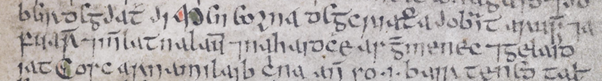

Fig. 2: Royal Irish Academy MS 445 (24 B 3), p. 39 (15th/16th century): instructions for washing the hands and face (Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen).

The word indlat is used in early language for the act of washing hands or feet but in later language it is also used for washing the face. The above remedy suggests that the hands and face can be brightened by washing them in well-sieved barley-flour that has been boiled in water and then cooled.

Folcud/folcad (eDIL s.v. folcud or dil.ie/23084)

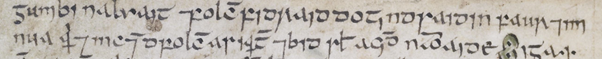

Fig. 3: Royal Irish Academy MS 445 (24 B 3), pp. 43-4 (15th/16th century): a cure for headache (Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen).

Folcud/folcad means ‘the act of washing the head’ but it can also be used to describe the liquid that is used for this purpose. This liquid is usually water that has been boiled or infused with plant material. Lye made from water, to which the ashes of plants has been added, is also used as an ingredient. Lye can also be mixed with oils or fats to produce a soap-like product.

The remedy to treat headache shown in Figure 3 above uses the word folcad in both senses. It instructs that one should place the well-crushed roots of plantain and nettle seeds on a red (hot) stone until they turn to ash. Lye, made from trees, is dripped on this along with fresh butter and the head is washed with it afterwards. It is claimed that the headache will be cured in nine days if one follows this procedure.

Fothrucud (eDIL s.v. fothrucud or dil.ie/24202)

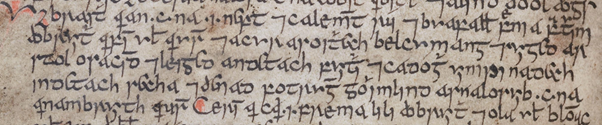

Fig. 4: Royal Irish Academy MS 445 (24 B 3), p. 74 (15th/16th century): a cure for bladder stone involving a medicinal bath (Image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen).

The word fothrucud often occurs in association with folcad. For example, in a description of the preparations made to welcome Conghal and his forces in the narrative Caithréim Conghail, it is stated that do rinnedh fliuchcaomhna foilcthe ⁊ fothraicthe dhóibh ‘a bath was made to bathe their heads and bodies’ (MacSweeney 1904, 82). The two words are also found together in a text called Cáin Domnaig, which lists activities which are forbidden on Sundays. These include shaving, washing (of heads) and bathing (ná berrad, ná folcad, ná fothrucud) (O’Keeffe 1905, 202–3).

Fothrucud, the word for bathing, is frequently found in descriptions of hospitality provided to guests but a bath can also be used to treat many ailments. Sometimes baths are prescribed in order to restore humoural equilibrium but equally hot baths are sometimes to blame for illness. A tract on pathology in King’s Inns Library MS 15 (p. 97v36) suggests that hot baths may be one of the external causes of opthalmia. However, provided that it is not a Sunday and the patient does not have an eye ailment, this remedy recommends a healing bath to treat haemorrhoids: add boiled roots of figwort to the bathwater, in which the patient is immersed up to the navel.

In addition to submerging and washing with water there are descriptions of treatments which call for steam therapies. For this kind of treatment, the patient absorbs the curative properties of certain ingredients by sitting over a vessel of steaming hot liquid in which herbs have been boiled. This treatment is often followed by a bath. This method of treatment is prescribed for menstrual problems and also for haemorrhoids. The remedy in the image below is for haemorrhoids and for that purpose catnip, calamint, rue, ragwort and the roots of figwort are boiled in wine or water and placed in a vessel with a narrow mouth. The patient sits on a stool over this vessel and is covered by a cloth in such a way that the steam cannot escape and then afterwards is immersed up to the navel in a bath with the same herbs, which have been boiled in water.

Fig. 5: Royal Irish Academy MS 445 (24 B 3), p. 74 (15th/16th century): a cure for haemorrhoids (image courtesy of Irish Script on Screen).

Further reading:

- Gray, Elizabeth A., ed. (1983), Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Mag Tuired (London: Irish Texts Society). Edition; Translation

- Hayden, Deborah (2024), ‘From the “King of the Waters” to Curative Manuscripts: Water and Medicine in Medieval Irish Textual Culture’, in The Elements in the Medieval World: Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Water, ed. by Marilina Cesario, Hugh Magennis, and Elisa Ramazzina, (Leiden: Brill), pp. 75–98

- Lucas, A. T. (1965), ‘Washing and Bathing in Ancient Ireland’, The Journal of the Royal Irish Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 95: 65–114

- MacSweeney, Patrick Morgan (1904), Caithréim Conghail Cláiringhnigh – Martial Career of Conghal Cláiringhneach, Irish Texts Society 5 (London: Irish Text Society)

- Meyer, Kuno (1906), The Triads of Ireland, Todd Lecture Series 13 (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co)

- O’Keeffe, J. G. (1905), ‘Cáin Domnaig’, Ériu 2: 189–214

- Ramazzina, Elisa (2024), ‘Bathing in Medieval Europe’, in The Elements in the Medieval World: Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Water, ed. by Marilina Cesario, Hugh Magennis, and Elisa Ramazzina, (Boston: Brill), 99–139

- Plummer, Charles (1922), Bethada Náem nÉrenn,2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press)