Deborah Hayden

Figure 1: Isidore of Seville, depicted by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1655)

The seventh-century author Isidore of Seville, whose encyclopaedic Etymologiae (‘Etymologies’) was well-known to Irish scholars of the early Middle Ages, gives the following account of the origins and founders of medicine:

Among the Greeks, Apollo is considered the author and discoverer of the art of medicine. His son Aesculapius expanded the art, whether in esteem or in effectiveness, but after Aesculapius was killed by a bolt of lightning, the study of healing was declared forbidden, and the art died along with its author, and was hidden for almost 500 years, until the time of Artaxerxes, king of the Persians. Then Hippocrates, a descendant of Asclepius (i.e. Aesculapius) born on the island of Cos, brought it to light again (trans. Barney et al. 2006: 109).

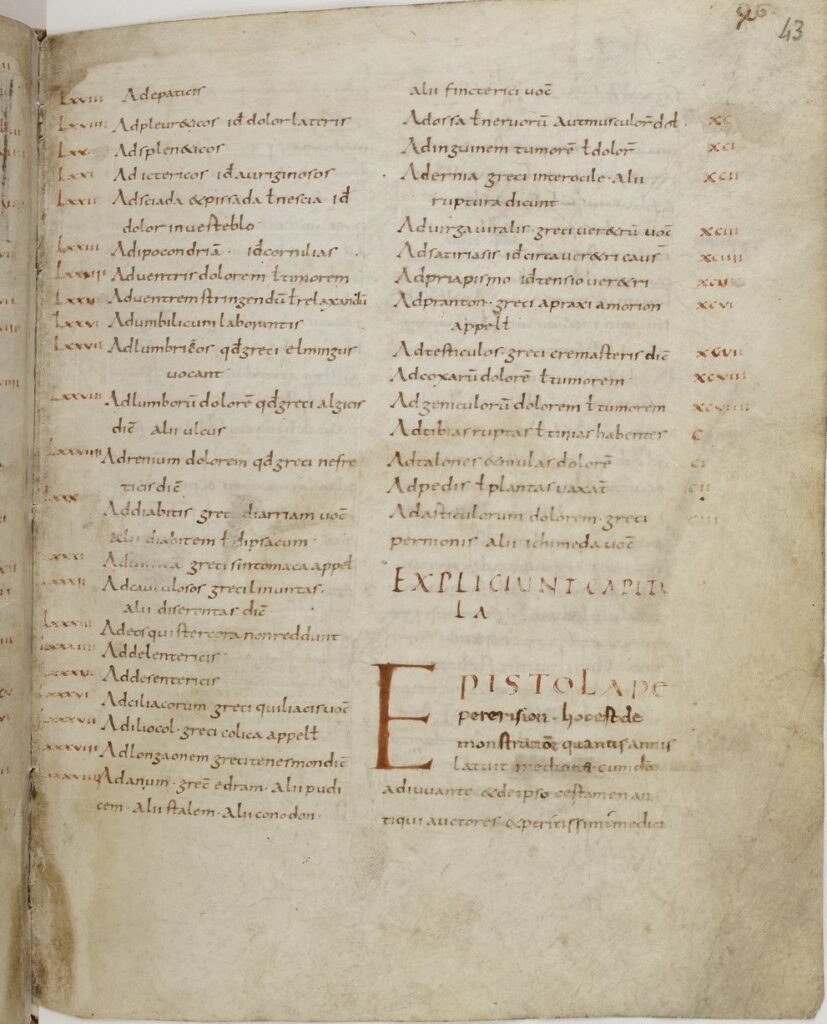

The scribes of medical manuscripts circulating in the Carolingian world some two centuries later provided similar accounts of the origins of medicine that drew on Isidore’s teaching, but also reshaped it to fit within the framework of Christian salvation history. For example, a text known as the Epistola peri hereseon (‘Letter on the Sects’), preserved in a ninth-century medical manuscript from the Abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris (see Figure 1), claims that ‘After the Flood, for 1500 years medicine lay hidden, right up to the time of King Artaxerxes of the Persians. Then Apollo, his son Scolapius, Asclepius the uncle of Hippocrates [and Hippocrates] – these four invented the art of medicine and the sects’ (Glaze 2007: 490; cited in Leja 2022: 130). Here, the pagan founders of medicine are neatly inserted into a narrative of human history that is premised on biblical events, such as the account of the Flood given in the Book of Genesis.

Figure 2: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS 11219, fol. 43r: a 9th-century Carolingian medical manuscript containing the text known as the Epistola peri hereseon (‘Letter on the Sects’).

Medieval Irish scholars were certainly no strangers to this broader European tradition of salvation history (for a recent exploration of this theme, see Boyle 2021). A wide range of sources from this region attest to a particular interest in legends relating to the ancient history of Ireland and the origins of its people, a tradition that culminated in the lengthy Middle Irish text known as Lebor gabála Érenn (‘The Book of the Taking of Ireland’ or ‘The Book of Settlement’). This work provided, as John Carey (1994: 1) has observed, ‘a narrative extending from the creation of the world to the coming of Christianity, and beyond – a national myth which sought to put Ireland on the same footing as Israel and Rome.’ Little direct information can be gleaned from the Lebor gabála about what medieval scholars considered to be the origins of the art of medicine (or, indeed, of other disciplines). The influence of the work can, however, be detected in an intriguing passage, the earliest extant version of which is preserved in a manuscript of the fifteenth or sixteenth century, that lists the names of individuals considered to be the ‘first physicians of Ireland’ (Meyer 1897). This passage was included in the preface to the great book of genealogies compiled in the mid-seventeenth century by the Irish antiquarian Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh, who presents it as follows:

Cédliaigh, ceudsháor, agus cédiasgaire do bhí in Erinn ar tus riamh .i.

Capa re legheas ní lag,/re remheas roba coimhneart,/Is Luasad an sáor glic gle,/agus Laighne an t-iasgaire.

Eaba .i. bainlíaigh, tainig ar áon le Ceasair, an liaigh tánaisi. Slanga mac Parthaláin an treas liaigh táinig la Partholán in Erinn. Fearghna ua Crithinbel an ceathramhadh liaigh tainig ar áon le Nemidh in Erinn. Leagha Fhear mBolg didhiu: Dub Da Dublosach, agus Codan Coim-cisneach, agus Finghin Fisiocdha, agus Maine mac Greassach, Aonghus an Ternamach. Leagha Tuaithe De Dhanann .i. Dían Cécht agus Airmeadh agus Miach, ⁊c.

The first physician, the first craftsman and the first fisherman who was ever in Ireland:

Capa, not weak in healing – /for a time he was strong – /and Luasadh the clever famous craftsman/and Laighne the fisherman.

Éabha, the female physician, who came along with Ceasair, was the second physician. Slángha s. Parthalán was the third physician, who came with Parthalán to Ireland. Fearghna s. Crithinbhéal was the fourth physician, who came along with Neimheadh to Ireland. The physicians of Fir Bholg also: Dubh Dhá Dhubhlosach and Codán Coimchisneach and Fínghin Fiseachdha and Maine s. Greasach, Aonghus an Téarnamhach. The physicians of Tuath Dé Danann: Dian Céacht and Airmheadh and Miach, etc. (ed. and trans. Ó Muraíle 2003, I.170–3)

The first two physicians cited in this passage are mentioned in Lebor gabála Érenn as antediluvian settlers of Ireland. It is claimed that Capa, Laigne and Luasad were Spanish fishermen who were driven to Ireland by a storm a year before the Flood; having seen the fertility of that land, they returned to Spain to collect their wives and returned to Ireland shortly before the Deluge, only to be drowned at Tuad Inbir (the estuary to the River Bann) without leaving any progeny (Macalister 1932-42, II.178–9, 184–5 and 198–9). The identity of one member of the trio as a wright and another as a leech only occurs, however, in one verse rendition of this account.

The details of the ill-fated visit to Ireland by Capa, Laigne and Luasad are scant and little else is known of these figures outside of the Lebor gabála tradition. By contrast, the association of the banliaig (‘woman leech’) Eba with Cessair – the daughter of Bith son of Noah who, according to Lebor gabála Érenn, had travelled to Dún na mBárc in the west of Ireland forty days before the Flood – is reflected in the medieval Irish corpus of place-name lore known as the Dindshenchas. There, it is recounted how Eba drowned after falling asleep and being consumed by the waves of the sea, thus giving rise to the placename Tráig Eba (‘Eba’s Strand’), which Gwynn (1903-35, IV.453) identifies as Machaire Eabha (Maugherow) in Co. Sligo:

Traigh Eaba, cidh diatá? Ní ansa. Día tanic Cesair ingen Betha mic Naoí lucht curaigh co hErinn. Tainic Eaba in banlíaidh léi, cho rocodail isin trácht, co robáidh in tonn iarom. Conidh de raiter Rind Eaba ⁊ Traigh Eaba dona hinadhaibh sin osin ille.

Traig Eba, whence the name? Not hard to say. When Cesair daughter of Bith son of Noah came with a boat’s crew to Erin, Eba the leech-woman came with her. She fell asleep on the strand, and the waves drowned her. Hence these places were called Rind Eba and Traig Eba from that time forth (Gwynn 1903-35, IV.292–3).

These origin legends concerning the unfortunate fates of the earliest medical practitioners in Ireland are reminiscent of the claim in the Epistola peri hereseon that knowledge of medicine was extinguished for a period of time following the biblical deluge. The return of such knowledge to that region, however, is represented by the third physician listed in the preface to Mac Fhirbhisigh’s genealogies: namely, ‘Slánga’ son of Partholón. The latter figure had, according to the Lebor gabála, led the second wave of settlers in Ireland after the Flood had caused the deaths of Cessair and her companions. It is claimed in another dindshenchas narrative that ‘Slíab Slánga’ – identified by Gwynn as the older name of Slieve Donard in the Mourne Mountains – was so called because Slánga was buried in that place by his father. The dindshenchas narrative claims that Slánga was the cétna liaigh Érenn (‘first leech of Ireland’) and that he ‘wrought healing in Ireland for [his brother] Laiglind, who was wounded in his place at the great battle of Mag Itha’ (Gwynn 1903-35, IV.298-301).

Figure 3: Stephen Reid, ‘The Two Ambassadors (of the Fir Bolg and Tuath Dé)’ (1910)

The other physicians listed by Mac Fhirbhisigh are likewise associated with the various postdiluvian invaders of Ireland whose activities are recounted in Lebor gabála Érenn. Of the three medical practitioners said to have belonged to the settlers known as the ‘Fir Bolg’, for example, the most famous is probably Fínghin Fiseachdha (‘Fínghin the physician’), who might be identified with a figure referred to elsewhere in medieval Irish literature as ‘Fíngin Fáithliaig’ (‘Fíngin the prophet-physician’). Although both the epithets associated with Fíngin may have simply been chosen for alliterative purposes, the term fáithliag likely alludes to the physician’s role in prognosticating the course of diseases. In the great epic tale Táin Bó Cúailnge (‘The Cattle-raid of Cooley’), Fíngin Fáithliaig is said to be the physician of the Ulster King Conchobar; when Conchobar’s warrior Cethern is grievously wounded in battle, numerous different healers are called in to help, but Cethern kills each of them when they predict that he will die from his injuries. Fíngin, by contrast, proves himself able not only to heal the warrior, but also to correctly identify the specific members of the enemy camp who had inflicted each of Cethern’s injuries merely by inspecting the wounds. Fíngin ultimately offers Cethern a choice: either that he treat his sickness for a whole year and allow Cethern to live out his full life, or that he give him enough strength quickly so that Cethern can fight his enemies for three days and nights only. In the true spirit of the heroic ethos, Cethern naturally chooses the latter course. Fíngin effects this marvellous treatment by creating a healing bath out of bone-marrow, giving rise to the place-name Smirommair (‘Bath of Marrow’, identified as Smarmore near Ardee in Co. Louth).

Of the ‘First Physicians of Ireland’ listed in the genealogies of Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh, however, those that are the best attested in the surviving medieval Irish literary record are the healers of the supernatural race known as the Túatha Dé: namely, Dían Cécht, Airmed and Míach. The first of these figures was commonly evoked as a medical authority in Irish manuscripts. For example, a seventh-century Irish law-tract on the compensation due to the physician for treating various types of injury, which survives in the fifteenth-century Irish medical compendium National Library of Ireland MS G11, is titled Bretha Déin Chécht (‘The Judgements of Dían Cécht’). Numerous cures in a medical remedy collection from a separate manuscript, compiled by a practising physician from North Connacht around the early sixteenth century, are likewise ascribed to this healer-figure.

Figure 4: John Duncan, ‘The Riders of the Sidhe’ (1911)

Dían Cécht famously appears alongside his children, Airmed and Míach (whose names, appropriately, are also attested as common nouns referring to dry measures) in the medieval Irish narrative Cath Maige Tuired, which tells of the contention between the Túatha Dé and the monstrous race of Fomoiri that culminated in a battle fought at Mag Tuired (Moytirra) in Co. Sligo. One episode of this tale recounts how Dían Cécht forged an artificial silver arm for the wounded King Núadu, only for Míach to surpass his father’s surgical skills by reciting a charm over the king’s damaged limb, thereby restoring its function in full. Dían Cécht then killed Míach out of jealousy and 365 herbs grew over Míach’s grave, which Airmed attempted to gather and sort according to their properties. Her father thwarted these efforts, however, by mixing the herbs ‘so that no one knows their healing properties unless the Holy Spirit taught them afterwards’ (Gray 1983, 32–33). It is possible that this passage reflects long-debated tensions surrounding the use of certain kinds of verbal incantations in preference to medicinal herbs for healing purposes. The final invocation of the Holy Spirit as the only power capable of determining the healing properties of plants recalls, moreover, the advice of the tenth-century English abbot Aelfric of Eynsham, who argued that ‘we should not set our hope in medicinal herbs, but in the Almighty Creator who gave power to the herbs’ and advised that men should not sing incantations over them, but rather bless them with God’s words (Clemoes 1997: 450; cited in Hindley 2023: 114).

The list of the ‘First Physicians of Ireland’ preserved in the preface to Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh’s genealogies may, in its earliest incarnation, have simply represented an attempt to summarise one small facet of the rich and diverse corpus of written lore concerning the origins of people and places in Ireland. It so also serves as a reminder, however, that although there are no surviving medical manuscripts from this region that were written during the early Middle Ages, we can nonetheless draw on a range of other types of sources to find glimpses of the role of medicine and healing in the wider framework of early Irish society and legend.

Further reading:

- Barney, Stephen A., W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof, trans. (2006), The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Boyle, Elizabeth (2021), History and Salvation in Medieval Ireland (London: Routledge)

- Carey, John (1987), ‘Origin and development of the Cesair legend’, Éigse 22: 37–48

- Carey, John (1994), The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory (Cambridge: Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic, University of Cambridge)

- Clemoes, Peter, ed. (1997), Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies: The First Series (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Glaze, Florence Eliza (2007), ‘Master-student Medical Dialogues: The Evidence of London, British Library, Sloane 2839’, in Form and Content of Instruction in Anglo-Saxon England in the Light of Contemporary Manuscript Evidence, ed. by Patricia Lendinara, Loredana Lazzari and Maria Amalia D’Aronco, Textes et Études du Moyen Âge 39 (Turnhout: Brepols), pp. 467–94

- Gray, Elizabeth A., ed. and trans. (1983), Cath Maige Tuired. The Second Battle of Mag Tuired, Irish Texts Society 52 (London: Irish Texts Society)

- Gwynn, E. J., ed. and trans. (1903-35), The Metrical Dindshenchas, 5 vols, Todd Lecture Series 8-12 (Dublin: Hodges Figgis)

- Hindley, Katherine Storm (2023) Textual Magic. Charms and Written Amulets in Medieval England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

- Leja, Meg (2022), Embodying the Soul. Medicine and Religion in Carolingian Europe (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press)

- Macalister, R. A. S., ed. and trans. (1932-42), Lebor gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, 5 vols, Irish Texts Society 34, 35, 39, 41 and 44 (Dublin: Irish Texts Society)

- Meyer, Kuno (1897), ‘Mitteilungen aus irischen Handscriften’, Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 8: 102–20, at p. 105 (‘Die ersten Ärzte Irlands’)

- Ó Muraíle, Nollaig (2003), Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh. Leabhar Mór na nGenealach: The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, 5 vols (Dublin: Éamonn de Búrca)